Alpha to the Omega: Z is for Zeno

By Samuel Chong

Z is for…

Zeno

“’Very truly I tell you,’ Jesus answered, ‘before Abraham was born, I am!’” (John 8:58)

“The Word became flesh and made His dwelling among us.” (John 1:14)

Who was Zeno?

Zeno was the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor from 474 AD to 491 AD. His reign was marked by political intrigue, military challenges, religious tensions, and the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD. Nonetheless, Zeno was credited with stabilising the Eastern Roman Empire, which would last for another millennium. In church history, Zeno is known for the Henotikon (“act of union”), which aimed to settle the controversy over the nature of Christ.

Background

The Roman Empire founded by Augustus had within 400 years grown too large to be governed by a single emperor from a single capital. The Empire was then split in half – the West and the East, each with its own Emperor and junior co-Emperor.

Zeno, originally named “Tarasis”, was born around 425 AD in the province of Isauria (in modern day Turkey). The Isaurians were considered barbarians by the Romans despite having been Roman subjects for more than 500 years. Faced with few options for advancement, Tarasis embarked on a military career and gained recognition for his military prowess and leadership skills. He soon caught the attention of the reigning Eastern Roman Emperor Leo I, who gave his daughter in marriage. To make himself more acceptable to the Roman elite, Tarasis adopted the Greek name “Zeno” after an earlier influential general/politician of Isaurian origin.

In 473 AD, Leo I proclaimed Zeno’s son Leo II (his grandson) as co-emperor, but died shortly after. At only 7 years old, Leo II was too young to rule himself and had to appoint his father Zeno as co-emperor. When Leo II died in late 474 AD, Zeno became sole emperor.

The Fall of the West

Weakened by years of barbarian intrusions, economic stagnation and corruption, the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD to the Germanic tribes under Chieftain Odoacer. Odoacer was content to rule Italy alone and sent an envoy recognising Zeno’s reign over the entire “reunited” Empire; in return Zeno recognised Odoacer as king of Italy. This peaceful arrangement avoided prolonged conflict with the Germanic tribes and allowed the Eastern Roman Empire to focus its efforts on preserving its remaining territories and ensure its survival until 1453.

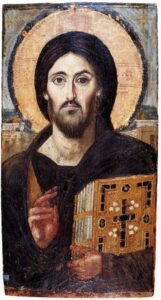

The Henotikon

One of the defining moments of Zeno’s rule was his issuance of the “Henotikon” (“act of union”) in 482 AD, an attempt to resolve the bitter religious dispute tearing apart the Christian East.

At the heart of the conflict was the Christological controversy between the Chalcedonians and the Miaphysites on the nature of Christ:

Chalcedonians | Miaphysites |

| Christ has two distinct natures (divine and human) that are united in one person, i.e. the hypostatic union* | Christ has only one nature, a divine-human nature |

| Adherence to the definition established at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD | Argued that the Chalcedonian definition threatened to undermine the unity of Christ’s person and emphasise His divinity. |

Zeno’s document aimed to appeal to both sides by avoiding use of controversial terms (e.g. referring to Jesus as just “The Son”). It also attempted to strike a balance by affirming the decisions of the Councils of Nicaea (325 AD – produced the Nicene Creed) and Constantinople (381 AD – confirmed the Nicene Creed) which established the foundational doctrines of the Christian faith, while avoiding any explicit endorsement of the Chalcedonian definition. Ultimately, both sides rejected the compromise – the Chalcedonians saw it as not explicitly upholding their doctrinal position while the Miaphysites felt it fell short of acknowledging their beliefs fully.

The Henotikon, although well-intentioned, exacerbated tensions rather than solving the Christological controversy, contributing to further divisions in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Conclusion

Zeno’s reign exemplifies the same theme explored in several past articles, namely i) the intersection of politics and the church, and ii) Christianity being a diverse arena of theological views and cultures. Despite its failure to achieve its intended purpose, the Henotikon is a significant episode in the history of early Christianity. It highlights the complexities of reconciling differing theological viewpoints and the challenges faced by emperors in attempting to maintain unity in a diverse and religiously divided empire. Christianity is not a monolithic entity, and theological disputes persist to this day.

This article was written partially with the help of ChatGPT, cross-checked for factual accuracy from the respective Wikipedia articles.

Further Reading

Concluding Reflections from the AuthorIt has been just over two years since I embarked on this project. Its poetic that the series started and ended with a Roman emperor (Augustus and Zeno); the Roman Empire, after all, holds a very crucial role in the development of the Church. I hope that readers appreciate that history is not straightforward, and always a lot more complicated, and we can never fully understand what happened. Nonetheless we should not shy away from reading more about church history (and history in general) and theology, even all the nasty and complicated bits. Thank you for journeying with me these past two years and I hope you have enjoyed reading these articles as much as I have enjoyed writing them. As to my next work, well, I think I shall go on indefinite hiatus until I can think of something worthwhile to write about (if you have suggestions, please let me know). |

Responses